The Need for Speed

Written by: Rik

Date posted: April 7, 2004

- Genre: Racing

- Developed by: Electronic Arts

- Published by: Electronic Arts

- Year released: 1995

- Our score: 5

What, given the chance, would you do if you had a selection of the world’s finest and fastest motor cars at your disposal? Well, you could drive to the middle of a town, dodge traffic jams and cause all sorts of mayhem, which could later be branded “auto-japes” or indeed, “auto-capers”. You might also become involved in some kind of crime gang as a getaway driver, using your knowledge of the city’s seedy streets and your background as an undercover cop to get you out of whatever scrapes come your way. Playing tag with the law around the grimy, claustrophobic city, never getting above fifty – hang on a minute, weren’t we talking about driving fast cars back there somewhere?

The reason that The Need for Speed appealed so much to me all those years ago was that it came up with the most logical of answers to the above question: take ’em to a very long, very straight section of road and drive them very, very quickly indeed. And while the GTAs and Drivers of this world are certainly fun, for me they really aren’t about driving at all. There was nothing high concept about NFS: no plot, no mission structure, no “go-anywhere” road system – EA just took one look at the much-loved Test Drive series and decided to give it a lick of paint.

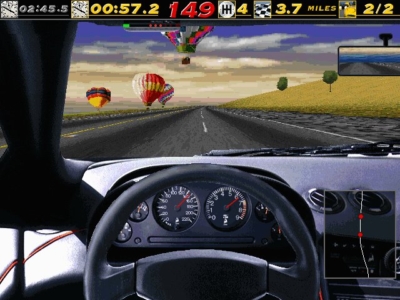

The graphics (obviously) aren’t as amazing as they once were, but some of the scenery remains impressive.

And what a lick of paint it turned out to be. When it first came out, NFS was absolutely gorgeous. It was one of those games which made you wonder whether graphics could be any better than this. The perfectly textured cars, the beautiful scenery, the well-rendered, er, roads – and all to a background of sampled engine sounds. To appeal to those who find cars sexually attractive, the menu screen also featured lots of pretty pictures of fast cars, with the opportunity to hear some voice-over man spout statistics about each of the featured vehicles.

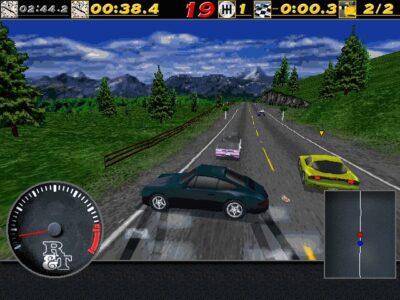

Several modes were included, but the only one most people cared about was the head-to-head road races. The aim was simple: outpace your opponent over three sections of road while avoiding civilian traffic and the attention of the police. A simple concept, brilliantly and professionally executed. Most people (myself included) were in car racing heaven.

Should you become involved in a collision, the game will automatically switch to the chase camera to give you a better view.

But would you play it now? Some nine years on, the gloss has definitely gone from the graphics, and the game’s shortcomings are altogether more apparent. Yes, the “invisible wall” surrounding the road is still there, you can’t really venture too far without hitting it, and if you try to turn around and drive the other way you won’t be able to see anything because the game doesn’t let you use the in-car camera. At the time, this was a small price to pay for the gorgeous graphics on show; now it just seems a little bit silly. On more tricky courses the cars’ handling seems too woolly and unresponsive, and twisty sections of track are difficult to navigate without that invisible wall coming into play.

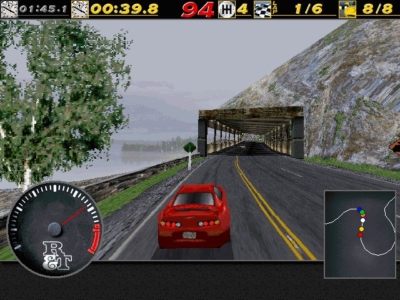

However, despite this, NFS still entertains. The thrill of the road race remains: there is a great sense of speed, facilitated by some very straight sections of road that really let you put your foot down. It’s in this respect that the original NFS lives up to its name, and also where its sequels disappoint. Need for Speed 2 was let down by the inexplicable removal of the police chase aspect of the game. The series got back on track with NFS 3 (and subsequent re-hashes – Road Challenge, Porsche 2000 et al), but the “feel” of the original had long since departed.

There’s no damage model, but high-speed collisions do result in some entertainingly spectacular crashes.

The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, the original NFS was never really about getting mixed up with the cops. The police chases were an inevitable result of you driving recklessly on public roads. By the third game, the patented EA gimmick-o-meter had turned the whole thing into some kind of police-baiting simulator. In NFS, the rules are simple: you pass a cop at over 55, the cop chases you until he manages to get in front of you, then you get a ticket. In NFS 3, you go over the limit and all of a sudden the whole force is after you, with tyre-slashing spike strips and the like. It changes the whole feel of the game, diverting attention away from high speed driving and towards nefarious cop-bothering.

Secondly, the road sections in the original NFS were just that – courses which started at one point and ended at another some three miles down the line. In NFS 3, what we have are a bunch of tracks wearing, ahem, “road trousers”. They look like roads, they have civilian traffic on them, but they’re laid out like a track – you even have to complete a certain number of “laps”, for crying out loud. It detracts from the sense of realism, more so than the aforementioned “invisible wall” that afflicted the original. Moreover, on some of them you can barely put your foot down because there are so many twisty, windey corners. I recall one review of NFS: Road Challenge asking, “why give the player a McLaren F1 if none of the courses allow them to get it out of third gear?”

I’m not trying to say that The Need for Speed is still one of the best racing games available. It isn’t. The graphics are dated, the handling clumsy, the opponent and police AI suspect, and the whole thing does feel a little “on-rails”. Despite what I’ve just said about the sequels, they are better games in almost every respect. But the original is one of the last racing games based around enjoying a drive on the open road. And if playing computer games is at least part wish-fulfilment, then the opportunity to drive some expensive sports cars on quiet country roads at high speed is surely quite a common fantasy. All we have to do is wait for the software companies to work it out (checks watch).

Posts

Posts