Cricket 96

Written by: Rik

Date posted: February 4, 2018

- Genre: Sport

- Developed by: Beam Software

- Published by: Electronic Arts

- Year released: 1996

- Our score: 5

Even the most determined of hardcore gamers cannot honestly say they have played All Of The Games, but there are times when you try to account for the gaps in your own gaming history and come up short. Sure, you can make a plausible-sounding argument as to why, for example, you never really played much Doom back in the day, but it sort of begs the question, what were you doing instead? If you weren’t playing the biggest and best, where did all that abundant free time go?

Firing up Cricket 96, it all came flooding back. From the opening video of what looks suspiciously like Glenn McGrath bowling an oversized cricket ball at some unguarded stumps, causing them to shatter, straight through to the familiar menu music and mildly eccentric spot effects, I remembered: this is the kind of thing I was doing. Whatever the best games of 1996 were, I was playing this instead.

Another thing that took up my time in the 90s was following the fortunes of the England cricket team, which seemed at times to have been deliberately calibrated to raise and then dash expectations in a sequence that would cause maximum possible disappointment. You’d never quite lose hope: there’d be moments of individual defiance, or collective brilliance, and occasional victories against the odds, but no period of sustained success, which always seemed to hang tantalisingly out of reach.

This led to some twisted and delusional thinking, which in my experience manifested itself either in an extended debate about selection between matches (we just need to pick the right combination of players!) or, when faced with an unfavourable match situation, like a miserable batting collapse, clinging onto the theoretical possibility that it could be somehow be turned around and that the last established batsman would build a mammoth partnership with a doughty tailender and rescue the innings (if these two stick together, we could get up to 400!) There were many distressing moments, but the glorious highs came along just often enough to keep you interested. It’s the hope that kills you.

(For more on this topic, Following On, Emma John’s look back on her own tragic obsession with English cricket in the 90s, comes with my heartiest recommendation).

Fans of cricket games have been forced to live in a similar state of denial, telling themselves that whatever dreadful title they’d wasted their money on was actually not so bad, and a mere couple of tweaks (perhaps from a forthcoming, never-to-be-released patch) away from being really good. My strongest feelings of this nature concerned the game in question here, which I knew as Ian Botham’s International Cricket 96 (the two games are to all intents and purposes the same, except for the title and some additional video clips featuring ‘Beefy’ himself), and that’s probably why the intro video and menu music seem so familiar, because it was so frequently abandoned and restarted.

In particular, batting first and setting a good total seemed to be a target that repeatedly proved beyond me, as I began patiently before losing my batsmen in rapid succession amid a blaze of irrational strokes. Was saving frequently and reloading cheating? Yes. But sometimes it wasn’t, if a dismissal seemed particularly unfair. Oh, the game could have been so good, if only for the fact that things that weren’t good kept happening and ruining it.

Cricket 96 is basically an updated PC version of Super International Cricket, which appeared on the SNES in 1994. One of the main differences is the inclusion of the kind of multimedia elements that people thought were impressive in the 90s: in this case, unnecessary video clips and annoying, context free commentary. Your commentators are fictional personalities Brian Richards (a composite of Tony Greig and any number of identikit matey Australian ex-players now pursuing careers in the media) and Gavin Dilley (an English bore seemingly based on Geoffrey Boycott). Their comments range from the extremely general to the largely nonsensical, and when it comes to the post-match analysis they seem to only have one set of remarks to make regardless of what has transpired. Their video appearances, meanwhile, quickly get repetitive, and it was only for the fact that I hadn’t seen them for 20 years that I resisted turning them off.

Super International Cricket‘s animated clips of player and crowd reactions have been ‘upgraded’ to video. In the former case this means witnessing a man in full cricket gear miming some shots in the manner of a teenager in front of the mirror (no, I never did that! Shut up, you’re stupid etc), an impression that even extends to the fact he seems terrified of knocking anything over with his bat (you can only assume the filming location must have been rather cramped). You can also witness a man pretending to be an umpire making various signals, including a dramatic slow raising of the finger, which is perfectly appropriate for upholding a marginal lbw appeal but not when a batsman has already been bowled or lobbed a catch into the outfield.

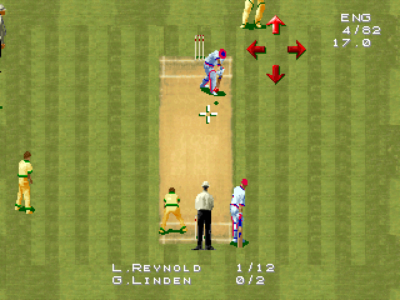

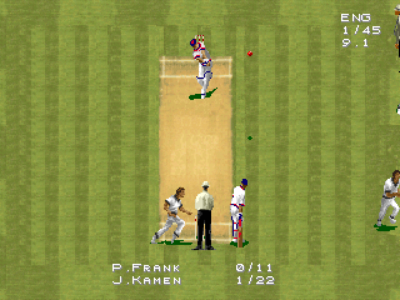

The action is quicker and more responsive than in Super International Cricket, although a switch to a two-button control scheme on PC necessitates some reworking of the SNES mapping. When batting, instead of pressing one of the four SNES face buttons to choose a shot, you choose direction using an on-screen indicator; one of the buttons toggles between shot direction and moving your batsman around the crease, the other executes the shot. Pressing both together launches a slog or aerial shot.

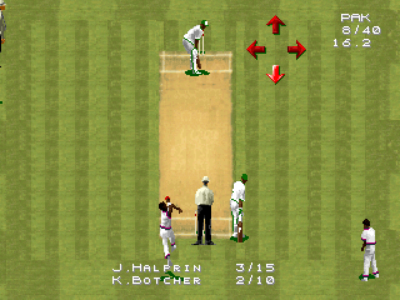

Bowling is similar: you preselect the type of delivery from the four available, use one button to toggle between that and selecting where the ball should pitch, then the other to start the run up and actually deliver the ball (buttons select a standard or slower ball, both together produces a faster one). While the compromise might sound a bit crap, it’s actually quite intuitive and overall, having played a little Super International Cricket for research, the trade off is worth it for the extra responsiveness.

Batting can be fairly enjoyable. The limited range of available shots does mean that there’s an element of automation about which shot is played, depending on where the ball pitches, and this can lead to some bizarre moments where the exact shot required is not executed: most commonly, when your batman chooses to duck a thigh-high delivery and play it with the side of his head. (And if this happens when you’re out of your crease, all opponents – and not just the Aussies – will unsportingly run you out). It soon also becomes apparent that shots to the off or leg side are likely to get you out under most circumstances, and there’s a particularly flappy off-side shot which seems to loop the ball in the air for a catch almost every time.

What this means is that you spend most of your time either driving the ball or defending, using your feet to work the ball down the ground and accumulate runs in a vaguely calming and enjoyable manner, aided by, it has to be said, some fairly idiotic and random field placings that, if adjusted, could soon choke off the flow of runs (as you yourself can choose to do while bowling). Big aggressive leg side swipes are enjoyable and do sometimes come off, but have a high risk factor. As ever with this type of game, there are loopholes and glitches that guarantee boundaries, if you’re prepared to employ such tactics and stand halfway down the pitch. (I’ve heard that typing IDDQD in Doom makes the game much easier, too).

As with most cricket titles, you can see where the ball is going to pitch before it’s bowled, so there’s an element of premeditation, although you do also have to watch the ball and get the timing of your movement and shot right. On the hardest difficulty, the cursor is removed, making batting, and in particular run-scoring, noticeably tougher. Each batsman’s stats affect how likely he is to play the right shot or occasionally edge the ball (most commonly, tailenders might fend the ball in the air when trying to defend a bouncer), while running speed is also a factor and can lead to vaguely comical mismatches with the quickest of batsmen almost able to lap the slowest. You can try to avoid marginal run-outs by pressing a button to slide in your bat (as we were all taught at school) or effect a dive, which is a nice extra detail.

Bowling, as ever, is not as much fun. If you sort of autopilot through it with a loose field, the opposition will smack you about a bit, but bring the fielders in and they won’t be able to get the ball away. As is the tradition, your bowlers can put the ball exactly where you want it, so keeping discipline is pretty easy. Satisfying cricket dismissals like bowled, lbw and catches in the slips are relatively rare, with opposition players more likely to flap the ball in the air and be caught in the outfield. Like the batting, it can feel a little inconsequential, almost as if the same ball could either get a wicket, be defended, or hit for four. There’s no such thing as a bad delivery: even if you deliberately bowl, say, a looping half-volley wide of the stumps, it’ll be patted back to you.

To maintain any element of challenge at all, you have to contrive your own rules, such as keeping to a preset field that allows your opponent some scoring opportunities. The hardest difficulty doesn’t do it: even though batting is harder for you, bowling doesn’t seem to be. In one Test match I played, fewer than 100 runs were scored overall – I was bowled out for 46 but then dismissed my opponents for 20. I still won, but it wasn’t much fun.

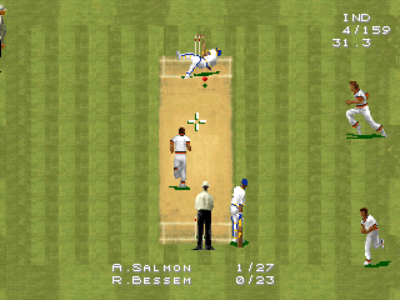

Fielding is semi-automated: catching and collection will be done for you but you have to choose which end to throw to and break the stumps if necessary. You can also use the direction controls to get a player to chase the ball more quickly, and a button press will effect a dive which is occasionally effective in catching or stopping a ball. Running speed is again a factor, and there is a fielding attribute too: those with lower abilities are more likely to drop catches. The way the fielding is done keeps you involved in the game but without making it a chore, plus there’s some comedy mileage in repeatedly throwing the stumps down. Combine this with the manual appeal feature and there’s plenty of childish fun to be had causing mayhem if you get a bit bored.

That all feeds into a sense of fun that makes Cricket 96 impossible to dislike. Looking back at the history of cricket games, I’d put them broadly into two camps: in the first, this and the likes of Brian Lara International Cricket 2005, which was similarly flawed but also accessible and, crucially, contained moments of excitement; and in the other, World Class Cricket, Brian Lara Cricket and EA’s cricket games of the 00s, seemingly aimed at those who like the tedious elements of the sport, like waiting for a bowler to go back to his mark, a batsman changing his gloves, or an extended rain delay. I say this as a fan of proper Test cricket: dullness isn’t the same as depth.

But, as a game, Cricket 96 doesn’t really work. It’s far too easy, even if you make allowances for the shoddy AI opposition. Available game modes are limited to individual one day internationals or Test Matches, or a World Challenge – a tri-nation limited overs tournament. For the most balanced challenge, a T20 is probably it, allowing the opposition to score a decent total, if you let them, and tempting you into playing more risky shots. (I did actually once lose a T20 game attempting to thrash away a relatively easy total). There was, back in the day, an unofficial utility which would create a save game with a preset total for you to chase, but sadly it’s disappeared from the web as far as I can see.

A final note: although this isn’t the most visually appealing game and does indeed resemble a SNES title from 1994, I must acknowledge the bowling animations, which I’ve long considered to be a thing of beauty. There’s the nippy fast bowler, racing up to the wicket and delivering a ball in a whirl of arms and legs; the bustling medium pacer, still capable of slipping in a quick bouncer; and the spinner with a busy action, ingenious in its ambiguity, that can pass for either finger or wrist spin. Compare with contemporary rival, Graham Gooch, in which bowling actions are only marginally more realistic than those in table-top cricket games where bowlers had a section of guttering attached to their arm; and even much more modern titles with supposedly motion-captured actions like Brian Lara Cricket and EA Cricket 2005, where players clomp up to the wicket like an old horse and deliver the ball with similar grace.

There’s a part of me that does still think Cricket 96 could have been really good. Beam Software’s follow-up, Cricket 97, for all that it hangs together better overall, somehow also represents a bit of a step backwards, suffering as so many did by switching from serviceable 2D to ugly 3D (weirdly flat players and, more significantly, aesthetically upsetting bowling actions were two particular low points). As for this one, it’s not a good game, but there are enough good moments to make it worth a few hours of your time.

Posts

Posts