ICC Cricket World Cup England 99

Written by: Rik

Date posted: November 10, 2023

- Genre: Sport

- Developed by: The Creative Assembly

- Published by: Electronic Arts

- Year released: 1999

- Our score: 3

It’s possible to overstate the extent to which the English cricket team was terrible in the 90s. Rather than losing all the time, they simply lost most of the time, while occasionally providing flashes of brilliance or moments of stern resistance that temporarily raised the hopes of supporters, only for them to soon be dashed again. By most standards, however, 1999 was the nadir: a home World Cup, during which they failed to progress from the group stages, followed by a defeat in the subsequent Test series to New Zealand, which ended with the team bottom of the world rankings and skipper Nasser Hussain leaving the field to a chorus of boos.

Beyond the home side’s performance, the 1999 tournament was notable for being a fairly embarrassing affair in general, particularly when compared to the glitz and glamour of its footballing equivalent. The opening ceremony saw Tony Blair half-heartedly introduce a damp and smoky fireworks display which largely obscured the flag-carrying children on the pitch, while Dave Stewart of The Eurythmics was commissioned to provide an official song, which was only released after England had been eliminated and failed to chart. Three Lions at Wembley, this was not.

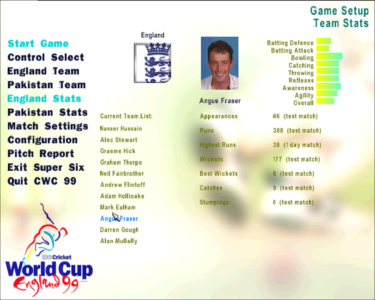

The nicely presented, but useless, stats screen. Phrases like ‘Highest Runs’ and ‘Best Wickets’ should ring alarm bells.

ICC Cricket World Cup England 99 was the first – and, to date, only – time a cricket game based specifically and exclusively on the tournament was produced, arriving as a surprise last-minute rival to the long-trailed and somewhat delayed Brian Lara Cricket from Codemasters. With the latter offering a World Cup tournament of its own alongside a full range of other options, including Test matches, the major selling point of EA’s effort was the official stamp of authority that comes with a major license – all the squads, decked out in the correct kits, playing at the official grounds, etc.

To that extent, at least, it succeeds. There are official squad line-ups, complete with player pictures; the kits are true to the (awful) real-life ones; and the full range of English county grounds featured in the tournament are represented. However, if you’re reading this review in the traditional fashion, you’ll have seen the score by now. In most other respects, it’s an effort in keeping with the standards of the tournament and England’s efforts to win the trophy.

But that’s not exactly the full story. Lots of elements of Cricket World Cup 99 hold up surprisingly well: it displays much more ambition than the likes of Brian Lara Cricket, is more exciting to play, and was arguably ahead of its time, serving as a precursor to rather more successful efforts in the subsequent decade. What it isn’t, unfortunately, is finished. In fact, it may be one of the most unfinished games I’ve ever played.

This much was obvious to me back in the late 90s, roughly ten minutes after installing the game. Without wanting to judge the professionals of the era too harshly, the scores of 80%+ awarded by both PC Zone and PC Gamer seemed at the time like significant errors of judgement, and in retrospect must surely have been based on unfulfilled promises that any glitches would be ironed out in the final release.

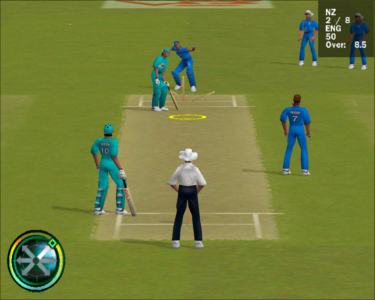

‘Welcome back, where New Zealand are 2-8 in the ninth over, chasing 50 to win, and goodness knows what else is going on out there…’

I can’t recall if I ever found or installed the official patch at the time, but the files are handily included along with the readily available downloads of the game available on The Internet, and I can confirm that their installation did very little to alleviate the significant problems with the game. The patch notes, however, are a bit of a hoot, and include phrases like ‘batsman no longer soils himself on the pitch’, ‘umpire now wears trousers’ and ‘bug whereby the entire enterprise seems futile and irrelevant now fixed’. [Are you sure about this? – Ed.]

Whatever is or is not improved by the patch, matches are still a bit of a comedy clown show, with players haring all over the place on a regular basis, making even regularly uneventful deliveries descend into the territory of Allan Donald’s famous run-out in the 1999 semi-final. Most notably, the wicket-keeper will run forward towards each ball like a madman before catching it in spectacular fashion, accompanied by a sound that sounds like the slamming of a car door.

Meanwhile, the process of appealing for, or taking, a wicket, includes no accompanying animations, with players so concerned about getting back to the relevant place for the next delivery that any theatrical questioning of the umpire or celebrations are unable to be countenanced. Long suffering cricket fans may well recall the brief release of Ashes Cricket 2013, which prompted a series of logic-defying YouTube gameplay videos, before being pulled from sale: I’m not sure this is quite that bad, but it’s in a similar kind of territory.

Rather than focus on all of the glitches, both major and minor, my approach was to simply brush them aside, set a full tournament going on middling difficulty, and see how it all went. In the first match, I bowled Sri Lanka out for not much, and then managed to knock the runs off in pretty reasonable time despite a combination of rustiness and pure incompetence making it much closer than it needed to be.

Bowling is actually quite good fun, particularly as it’s easy to have a lot of success: fast and medium paced bowlers have a full range of deliveries at their disposal and can swing or seam the ball both ways without much effort; they can also, as was the long-running tradition, bowl it exactly where you indicate, with the only concession to the challenges of the real-life sport being that a) you have to judge when to release the ball for maximum pace, otherwise you’ll be punished with a reduction and b) if you don’t get the bowling marker in the right place when you start, moving it during the approach becomes a bit more tricky.

Otherwise, though, you have the ball on a string, like Glenn McGrath at Lord’s on one of his really good days, so of course you can run through opposition teams (who are powered by rather dimwitted AI that seems to be surprised when you bowl at the stumps) at will. Batting, meanwhile, involves a directional cone that must be altered during the bowler’s run-up, with the option of playing a defensive, attacking, or super-aggressive shot, and you having the advantage of seeing where the ball is going to be bowled in advance.

You can move your player closer towards the pitch of the ball, too, and even if you do so the bowler will not adjust his aim, again skewing things in the player’s favour, although things are evened up slightly by the lack of specificity in shot selection, meaning your player occasionally attempts a completely inappropriate stroke, despite your best intentions. In general, it all represents a kind of midway point between EA Cricket 96 and Brian Lara International Cricket 2005 in terms of approach, which, in my view, is broadly a good thing.

Still, the opening match lasted less than half as long as it was supposed to, with scores well below 100, which was hardly ideal. The situation further deteriorated with the realisation that the restoration of a saved game somehow causes the activation of ‘Expert mode’ during which the ball marker is no longer visible while batting. This makes scoring runs virtually impossible, particularly as the control system means that the movement of the batting cone involves the use of one of the buttons that also executes a shot, leaving the only alternative to simply guess where the ball might land in advance and pick the least risky option.

This development meant that carefree experimentation with different bowling deliveries, in the safe knowledge that any total was likely to be attainable, went out of the window in favour of ruthlessly attacking the stumps. Meanwhile, sensible batting had to be eschewed entirely, with runs mostly achieved through risky singles taken from defensive lunges, mixed with the occasional risky slog. If nothing else, the sense of tension, which had previously been absent, was restored with a vengeance, as events devolved into a series of ultra-low-scoring shoot-outs: bowling opponents out for less than 40 and then worrying about how on earth you’d ever get that many yourself.

Still, it wasn’t exactly cricket, either. Or at least not cricket played by professionals in a global tournament. In a group match, I managed to bowl Kenya (admittedly, not a Test-playing nation, but still) out for 0, without necessarily spamming one particular delivery. So potent were my opening bowlers of Angus Fraser and Alan Mullally (both of whose international careers in real life failed to last much longer than this tournament) that there was rarely any need to call upon anyone else, although to be fair I did notice that ‘bowler fatigue’ actually seemed to have an effect after a few overs, and occasionally Darren Gough or Mark Ealham would have to be called upon to finish things off.

Despite some iffy moments, I did actually win the World Cup, which came as a surprise, given that there was no acknowledgement of the final in the presentation or the commentary, with only a video at the conclusion of yet another very brief match serving as notice that all my dreams had indeed come true and my quest was at an end. (The commentary, incidentally, is at odds with the rest of the game, with the laid-back then-BBC combo of Richie Benaud and David Gower offering generically calm and professional analysis of a completely different match to the pure chaos unfolding out on the pitch.)

‘He’ll have to be quick!’ says the commentary – and you do, because the fielders hit the stumps almost every time.

A switch to single matches at least allowed the game to be experienced with the settings as originally selected (mid-match saves not being an option at any stage of the game, which would be problematic in itself if games lasted as long as they’re supposed to). There is also the option to cede control to the computer, and one possible option for contriving a decent match is to let the fielding play out by itself, leaving you with a hopefully more significant total to chase with the bat (by which I mean, they score about 150 and are bowled out in about 20 overs, so still well short of what you’d expect in a real match).

However, it soon becomes apparent that scoring options are still fairly limited. When bowling, the AI opposition tends to seize on any slightly misdirected deliveries in one of two ways – a massive slog-sweep over square leg for six or a big hit over the bowler’s head – with these forming the bulk of their totals, along with a few scraped singles. When batting, your scoring patterns are similar, except the big slog-sweep appears impossible to effect, so the hit down the ground is your only big shot – or at least the only one where you can be sure that your batter will execute the stroke that you intended. Otherwise, a combination of an erratic interpretation of your wishes and the frankly strange behaviour of the ball (bouncers can go straight along the ground, while loopy slower deliveries do the opposite) undermine your attempts to play a wide variety of shots with any success.

It’s a shame. Batting and bowling are much more fluid than in contemporary titles, and the motion-capture, from the Hollioake brothers and Surrey wicket-keeper Jonathan Batty, is very well done. Strangely, given their relative strengths as players, it appears to be Adam Hollioake’s action that’s been used for the seam bowling (the late Ben having a very distinctive chest-on approach that was used in EA’s Cricket 2002) but nevertheless, it’s a thing of beauty, even though the deliveries themselves are rather too similar to Hollioake’s assortment of slower balls and cutters, no matter who is actually bowling. (And spinners are sadly even less well represented).

Even if, having made your peace with players running all over the place in a crazy fashion, you find yourself admiring some of the potential on display, you’ll still receive other reminders – the bat connecting with ball making a weirdly insignificant noise, almost as if Dennis Lillee’s infamous aluminium bat has been brought back from the early 80s, or the stumps being demolished evoking thoughts of a 10-pin bowling alley – that things are not as they should be. And that’s before you look at the scorecard and realise that you’re 12-7 chasing a total of 25. By most objective measures, this is a game that has completely failed to achieve what it set out to do.

EA being EA, it subsequently released a little-changed update to this title the following year, called (obviously enough) Cricket 2000. Despite having no tournament-based excuse for doing so, one day cricket remained its sole focus, and from memory there was little evidence of any of the significant issues and bugs being ironed out to any great extent (possible review: pending). Rather than sticking with the bones of this game, they then went in a different direction, releasing a series of rather stodgy efforts, of which the functional but execrable Cricket 2005 was a representative mid-point. It was – and I will repeat myself here – a great shame.

Clearly, you’d have to be of slightly unsound mind to be dusting this game off and expecting to get any significant enjoyment out of it. Until recently, I was convinced that it could not be made to work with modern Windows, and I’m still not really sure that it does – it refused to start maybe 50% of the time and often crashed upon saving. But there’s definitely something there – perhaps only for people like me, who bought it at the time and felt keenly the sense of squandered potential that seems oddly appropriate for a cricket game set in late-90s England – that makes it worth the trip back in time.

Posts

Posts