I occasionally see complaints from those involved in game development expressing irritation that those playing or reviewing their games make sweeping statements about poor design or bad coding without having the first clue about either. Even though we’re in a quiet and extremely uninfluential backwater here, I daresay we’re guilty of making such statements on occasion too. Notwithstanding the fact that criticism of the end product is valid without necessarily being a criticism of the individuals involved or the amount of effort invested, it’s easy to forget how hard it is to put something together that works, never mind something that is critically and commercially successful, on time and within budget.

Like many people, I made the mistake of thinking that playing games bestowed me with the qualities required to make one, and during a certain period in my late teens, any shareware or commercial software that advertised itself as being “user friendly”, or not requiring you to learn any kind of programming language, became of particular interest. One early example was a programme called Illuminatus, which was actually presentation software (I think), but allowed sufficient interaction to cobble together a fairly terrible choose-your-own-adventure type affair with whatever hand-drawn graphics you could muster using MS Paint. Even so, I can’t recall actually producing anything with it, just a collection of half-baked and unfinished ideas that likely included far too much adolescent humour.

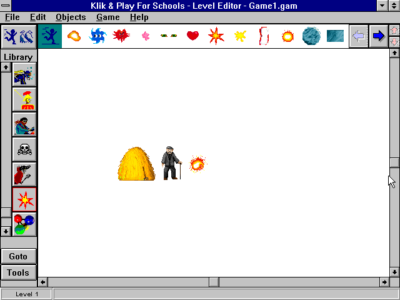

Klik & Play by Europress was a more appropriate piece of software for my purposes, as it focused on the easy creation of functional games, without the need to draw your own graphics or learn much in the way of code. I’m not sure if it was actually possible to make anything good, but it certainly made the process of getting stuff to move around the screen and interact with other things very easy indeed, and as such I spent more time than is healthy beavering away on a succession of unoriginal and highly unentertaining freeware titles for Windows 3.1.

Attempt 1 certainly didn’t lack ambition: my intention was to create a space shooter with an epic storyline, inspired by the likes of Wing Commander. And, like WC creator Chris Roberts, my focus was mainly on the story and cut-scenes, with the idea to staple on some generic 2D space shooter action afterwards.

Of course, I soon realised that I had neither the artistic nor technical skill to produce anything visually appealing, or anything that even actually worked, and the whole endeavour was soon abandoned not long after I’d begun trying to draw blue flight suits over the clothing of the stock character sprites.

Normally, this would have been the point at which I’d have given up entirely. But, after scaling back my expectations somewhat, I nevertheless persisted to the extent that I managed to produce four rather basic attempts at entertainment:

1. One-on-One Indoor Footy

Possibly my most successful title, in that I once saw two people I didn’t know playing it on one of the school computers, this was a largely plagiarised title heavily inspired by one of the bundled games, Go for Goal! (a title sadly not included in the version of Klik & Play currently available on the Web, but a quick Google does confirm its existence).

Like many of the bundled games, Go for Goal! was largely rubbish, and without minimising the scale of my theft, I think my changes did improve it. The original had giant players lumping a ball around a small pitch with goalkeepers moving about at random – it was less a football game and more a series of random collisions. My plan involved reducing the size of the players relative to the size of the pitch, turning the green playing surface to the colour of an indoor five-a-side arena, and removing the goalkeepers (I might have fiddled around with the ball behaviour parameters a bit as well).

Add to that a cheesy title screen using an image of ex-Leeds striker Toby Yeboah, a playful homage to the EA Sports “It’s In The Game” intro that was ubiquitous in the 90s (I recorded my own voice and increased the speed a bit so I sounded like a cartoon hamster on helium), and some player commentary by Barry Davies nicked from Actua Soccer, and you had the finished product. Hey, if you wanted to play a one-on-one indoor footy match between Gianfranco Zola and Dennis Bergkamp during which shooting was banned altogether, this was your only choice.

2. Road Rage In The Car Park

It went downhill from there. My next effort possibly started life as a genuine attempt to make a top-down racer, a genre that seemed within the bounds of possibility and actively supported by Klik & Play, based upon the library of pre-supplied graphics and sound packs provided and, yes, another demo game called Racing Line.

Racing Line was also pretty crap, kind of like a worse version of [8-bit budget racer] Grand Prix Simulator by Codemasters, but as with all of the demo games provided, it was also much better than anything I could come up with myself. My intention was to come up with something similar, but from scratch, rather than repeating the previous exercise of taking an existing game and fiddling about with it a bit.

From memory, despite taking a close look at the workings of Racing Line, I couldn’t work out how to make the lap counter function properly, and the whole concept was swiftly abandoned on favour of a “comedy” caper in an enclosed car park, in which the only thing to do was drive into parked cars to increase your score while a MIDI version of some classical music played in the background. Each collision was accompanied by a sample of Homer Simpson saying D’oh! that was nicked from the Internet. Reader, it was absolutely awful stuff.

3. Club Simulator

One of the great things about not being young any more is that the pressure to be cool has dissipated completely, and if you weren’t cool at the time that it actually mattered, the release of that pressure comes as blessed relief. When you actually are young, though, not being cool can be the source of a great deal of bitterness and barely-suppressed anger, and on the evidence this particular K&P effort (ironically as uncool a weekend activity as you can get), I clearly decided that contemporaries who did ‘grown up’ things like go to festivals or nightclubs were a deserving target of these emotions.

I have clear memories of trying to create Glastonbury: The Game, possibly fuelled by my furious reaction to Radiohead’s seemingly never-ending set in 1997 dominating the BBC coverage. (I’ve long since got over it, and any hatred towards the band or any individual members, but at the time the very sight of Thom Yorke’s face would send me into fits of apoplectic rage). Anyway, MIDI covers of Britpop hits were sourced from the web, but once again, the lack of appropriate stock graphics, or indeed any real idea what the game would actually involve (probably something dull and boring which could be spun as a satirical commentary about how festivals aren’t actually that good) undermined progress.

So instead work began on Club Simulator, which recreated the disorientation and confusion of a busy nightclub with a static screen grab of a psychedelic flashing screensaver and some generic house music punctuated by another voice-over (yours truly, affecting a cockney accent and once again making use of a sound editor’s speed-up function). The aim of the game was to build up your ‘death meter’ by drinking, taking drugs, and dancing (here achieved with a click of the mouse, although the rules of the game dictated that you couldn’t just hammer one option repeatedly, you had to choose a different activity each time). Death could be achieved more quickly by getting fairly wasted and then clicking on the ‘Start Fire’ option, but if the ‘death meter’ wasn’t high enough at the time, then it wouldn’t work and valuable seconds would be lost.

You may infer from analysis of this setup that this game’s creator had adopted a disturbingly puritanical, right-wing tabloid view of youth culture without ever having been fully exposed to it, but that’s not the case at all. Coincidentally, though, I do now believe that all nightclubs are awful and should be closed down.

4. Rik Hard: The Game

In real life, no-one has ever called me Rik, and I’ve certainly never referred to myself by that name. As with anyone else who acquired a nickname as a youth, I’ve often wondered how it still seems to be attached to me, but am powerless to do anything about it without sounding like I’ve started taking myself extremely seriously (like when ex-Manchester United striker Andy Cole started insisting on being called Andrew) and/or having a better idea for a replacement.

Anyway, the etymology of the name is that, after getting a very short haircut aged 15, some wag at school joked that its severe appearance had been part of a wider transformation from standard mild-mannered nerd into some kind of hard-man nutcase. And with the word hard being the second half of my actual first name, and Die Hard being a popular action movie, my new moniker was created.

For completely logical reasons, a spin-off game inevitably (?) followed. Once again, the ambitious blueprint of a working piece of entertainment was scaled down into altogether more pointless territory, as Rik Hard: The Game saw the eponymous hero, viewed from the top down and possibly based on one of the One-on-One Indoor Footy player sprites, running through corridors and shooting crates, which then exploded. There might have been a time limit. No German terrorists were harmed, or indeed were featured. Again, it was very bad, but also took quite a lot of effort to produce [remind you of anything else? – FFG reader].

5. Untitled Exploding Grandpa Trivia Game (Incomplete)

Well, the title tells you most of what you need to know, really. Quite why I wanted to make this game, I’m not sure. What I do remember is that the player character had to approach one of two haystacks at either side of the screen, at which point an old man would leap from behind the haystack and present the player with a trivia question.

I can’t remember whether the Grandpa was meant to explode upon hearing the correct answer or the wrong one, but it didn’t matter because I mucked up the triggers in Klik & Play and the Grandpa exploded immediately after leaping from behind the haystack, and then reappeared and exploded again, regardless of what answer you selected. The project was swiftly abandoned thereafter, along with any plans for future titles.

—

I guess you have plenty of time to waste as a youngster, even if it doesn’t necessarily feel like it at the time, and perhaps the mild comedy value of each game, combined with the certain knowledge that a future in game development would not be for me, represented a decent return on my investment. But that would be a bit of a stretch, and certainly not enough to save these awful games from the Vault of Regret.

Klik & Play can currently be found on archive.org and needs Windows 3.1 to run (this can be done via DOSBox).

Posts

Posts

“sweeping statements about poor design or bad coding without having the first clue about either.” : this is *not* an argument. I can’t sing, *ergo* I’m not qualified to say that Madonna is a poor singer ? Michael Jackson is supposed to have sold much more CDs as Mozart, *ergo* the moonwalker is better than the freemason ? I’m not a director, *ergo* I cannot say Karajan is *sometimes* overrated ?

D’you think critics in music have to be even average musical performers ? D’you think literary critics have to be able to write novels ?

Sorry, pure nonsense. You don’t have to be a star in one domain in order to judge its products, provided you have brains : experience, logic and common sense.

It *can* help to know a little of the craft you have to judge, but it is not the guarantee the final advice will be valid. Anyone with a decent I.Q. and experience of the world can judge anything, provided one can give good *reasons* for this judgement (without any factual justification, a judgment is just an opinion).

I’ve been in computer developement (a few commercial products and a few freeware), and I’ve been in the computer press : I’ve seen everything, from bozos giving silly advices because they were bozos, to clever people giving good reviews even without being programmers, and between the two, I’ve also seen normal people giving average advices while having a little acquaintance with software development. By the way, the best reviews were not made by programmers but by people learned in Latin classics.

If only game programmers are allowed to rate games, the result won’t be pretty, especially if they’re lousy programmers and adepts of poor “but so cool” design.

By the way, I’ve played about 2000 games in many categories (yes, I had time to waste at a time). This also gives experience in order to rate them.

“criticism of the end product is valid without necessarily being a criticism of the individuals involved or the amount of effort invested” : sorry again, but this is politically correct nonsense. This is what we call in French criticizing the game and the cards, but avoiding to criticize the players. This is definitely odd. The players *are* responsible for what they do, which allows for criticism of they final product, whatever the efforts and the time taken. Efforts and time taken are *internal* affairs the final buyer is not interested in. What does matter is : is the product *good* or *not* ? One does not have to care about it produced in six months or three years, by 5 talented people or by 50 suboptimal programmers, artists and designers. You have to judge the product, and if it’s bad, the responsability is on its producers, whatever the excuses (and I know quite a lot of them, having written an automatic excuse generator !).

Else, one must hide the names of producers and even, why not ?, publishers.

The key to avoid bad criticism (again, *with* reasons clearly stated) is to make good products.

July 6, 2019 @ 8:37 am

P.S. : I forgot one amusing argument. Though I’m no longer interested in games (whether as player or as developer or even as observer of the scene), seems nowadays, many game developers ask their future customers what they would like in the games they’re designing or writing (hence the pre-alpha reviewing and the like, if I’m not entirely mistaken).

So, the designers themselves are so *unsure* of their design and ideas they try to submit them to a form of pre-criticism or whimsical opinions *before* creating the real product. Yet, as far as I know, not that many gamers are qualified (even as good gamers) to give their argumented advice about level design, story, artistic choices and the like. Yet, publishers do ask for these advices, for commercial reasons. Call that odd. 😉

D’you think a novelist should write a draft, submit it to readers, and take their advice into account ? I’m not sure you’ll get masterpieces at the end.

D’you think we would have had Thief Dark Project (or Planescape Torment, or Tron 2.0, or Dungeon Keeper, or Psychonauts, or any other great game) if their talented teams had asked future possible customers their “buyer”‘s advice ? I guess we would have had pretty but ininspiring final games.

If you’re a great designer, you’ll be successful in making your clever ideas become a classic because no one else did the same (or did it as well) before. Ask the audience what they want, and you’ll end producing ordinary trash.

The “if you’re so smart, write your own game instead”, this was a sentence targeted to software Apple ][ pirates, not to regular customers. 😉

July 6, 2019 @ 9:02 am

Well, this was meant to be a silly piece about my own terrible efforts trying to make a game but…

A lot of effort can go into creating something that turns out to be rubbish. That doesn’t mean critics or consumers can’t say it’s rubbish or that they have to acknowledge that effort.

If I thought technical expertise was required to criticise games then I wouldn’t be a lifelong fan of writing about games, or have been doing so myself for all of these years!

July 6, 2019 @ 10:25 am

Seems (unless I’m mistaken) you agree with me, after all. Therefore, the two sentences I spotted, *quoted* and reacted upon (in poor English, but I’m melting when temperature is over 20 degrees, and it’s 30 degrees here) really did not belong to your amusing paper, especially since you’re the overqualified proof they’re wrong ! 😉

— a regular FFG reader (who has dropped reading now politically ubercorrect RPS)

July 6, 2019 @ 4:27 pm

Zola!

Zola!

Bergkamp!

Zola!

July 8, 2019 @ 10:26 am

Anyway I think we can all appreciate that games take a lot of work and skill to create, but also that you don’t need to be a programmer to offer a critical opinion.

July 8, 2019 @ 12:48 pm

Stoo, please would you be kind enough as to explain the *vis comica* or cultural reference of Bergonzola ?

Agreed. Therefore, these sentences were irrelevant as well as wrong : “sweeping statements about poor design or bad coding without having the first clue about either.” and “criticism of the end product is valid without necessarily being a criticism of the individuals involved or the amount of effort invested”

😉

Now eagerly waiting for next review.

July 8, 2019 @ 5:39 pm

heh, just a veeeery old injoke. I remember the commentator in One-on-One Indoor Footy shouting the name of either player whenever they kicked the ball.

July 10, 2019 @ 12:38 pm

As you’d expect, the commentary ‘feature’ was, like the game, very rudimentary. I set up a sound file of Barry Davies saying each player’s name (stolen, as mentioned above, from Actua Soccer) to play every time they touched the ball.

However, as they were never actually in possession, and the action was based around a player punting it slightly ahead of them, catching up with it, and then doing the same again, the names would be repeated far too often. Imagine a real match where the commentator felt obliged to mention a player’s name each and every time they took a touch…

Extremely irritating stuff, which is probably why it stuck in the memory for so long!

July 10, 2019 @ 3:31 pm

Thank you, Stoo. Now, that’s what I call a private joke — at least for us sport haters. 😉

July 10, 2019 @ 3:39 pm