As part of the site’s 15-year anniversary, I’m doing a few articles looking back at games I covered for FFG in the early days. They’re not the usual reviews or discussion pieces but hopefully you might find them interesting. The first piece, with a bit more explanation, can be found here, and all of the articles in the series can be found by clicking here.

This week, we’re looking at Blade Runner, and I should warn you that there are some mild spoilers for the early stages of the game (as well as for my never-to-be-published autobiography) ahead.

Like many 18-year-olds going off to university, I had agreed with my girlfriend that we’d keep the relationship going. And, like many 18-year-olds who make that agreement, we decided to break it off during the first term. These things are never easy, but it was all reasonably well-intentioned and certainly not, from my point of view at least, hastened by a new-found desire to embrace a hedonistic lifestyle. The days and weeks that followed were characterised by significant amounts of moping around.

The first year university environment was not the healthiest for processing emotions. Of course, there were distractions aplenty, and I’d made a few friends, but no-one that I knew well enough to talk about things with any significant amount of seriousness (mentioning my break-up to older colleagues from the student newspaper put me on the receiving end of some good-natured but rather robust mickey-taking). As my course involved a paltry number of contact hours, I spent a lot of time alone.

I had no internet and no TV, and to access either I had to make use of communal facilities like the extremely over-subscribed (and incredibly hot) computer lab or the common room, which was inhabited by slightly weird young men who liked to sit in there all day watching daytime quiz shows like 15-to-1. Hence, my ageing beige PC was pretty much the only place to turn.

At some point I decided to try and cheer myself up by buying a new game. Limited by budget and the extremely low spec of my PC (the family had recently upgraded so, having lived a fairly sheltered existence, I felt a bit annoyed at being lumbered with the old machine, until I actually got to university and realised how lucky I was to have a computer of my own at all), nothing especially took my fancy, so I ended up buying something that I’d already played and completed: Westwood’s Blade Runner.

There were a couple of legitimate reasons for purchasing another copy: firstly, the one I had at home was a special DVD edition that had come bundled with the new PC, and with DVD being fairly new in those days, I needed the original multi-CD release in order to play. I had also rather rushed through things the first time, even resorting to a walkthrough in order to navigate some of the trickier bits towards the end, most probably because I was playing at a time when I really should have been revising for my A-Levels [and because you’re a filthy cheating scumbag – FFG reader]. Nevertheless, it was still the first time I had bought a game twice, and it felt a little bit strange to have done so: I already (as ever) had a large portfolio of unfinished titles in my back-catalogue, and Blade Runner was one of only a handful that I had actually made it to the end of.

But I had a strong urge to play it again, and the main reason was nothing more than a vague sense that doing so might make me feel better. Just as you might seek reassurance or solace in repeat viewings of an old film, or listening again to a favourite album, I wanted to play that game I’d finished before because I liked it the first time around, and – notwithstanding my own tactics in completing it or the feted multiple endings – I thought that I would enjoy it again. Plus, the tone of the game seemed to fit my mood: a bog-standard racer or a mindless shooter just wasn’t going to cut it.

My first playthrough had fuelled an interest in the film, which in time I came to love and admire (as every correct-thinking person should). But because I had played the game first, and it had been my introduction to that world, a slightly disproportionate fondness for the spin-off lingered. In fact, during one of my many misguided pre-FFG plans to ‘build a website’ one of my article ideas was a piece in which I would claim that the game was in fact superior to the film. Thankfully this plan never came to fruition (unlike my decision to use the family AOL space to create a website in MS Notepad dedicated to reviewing all of the football games I could think of, regardless of whether I’d played them or not).

Still, while Blade Runner is certainly flawed, by sharing some of the same themes as the source material, it stood out to me at the time as one of the more thought-provoking games that I’d played. The game’s protagonist, Ray McCoy, is forced to ask himself many of the same questions as Harrison Ford’s Deckard, one of which is: am I the good guy, or the bad guy?

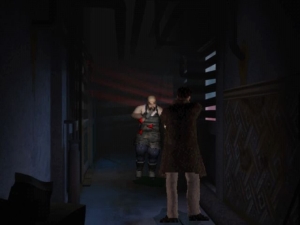

Like Deckard, McCoy starts off with some sense of certainty that what he is doing is right, but it doesn’t take long for that certainty to be eroded. One section that always stuck with me was an early confrontation with Zuben, the chef from Howie Lee’s restaurant and Clovis’s accomplice during the animal murders shown in the game’s introduction. He makes a run for it during questioning, and after chasing him down he eventually comes at you with a meat cleaver. Having been thoroughly prepared for the possibility of combat by the ready availability of a weapon, an opportunity to practice at the police HQ shooting range, and a lifetime of gaming telling me that violence is usually the answer, I had no hesitation in shooting Zuben dead.

There was no big red message saying what I’d done was wrong and not permitted; no big text written across the screen, stating HERE’S WHERE YOU MAKE A CHOICE, so I’d assumed I’d merely done what I was supposed to. But McCoy has a note of remorse in his voice when he recovers Zuben’s ID: “I’d retired a war hero, someone who’d fought for the freedom of the off-world colonists.” Suddenly, I wasn’t so sure.

Leaving the scene, McCoy encounters fellow cop Gaff, who offers congratulations but also asks if you performed a Voight-Kampff test – to establish whether Zuben was a replicant – before ‘retirement’. The answer, of course, is no: in the event, it doesn’t matter, because he was definitely a replicant (although this can vary for some characters each time you start a new game, Zuben is always a replicant) but, as Gaff reminds McCoy: “You ever retire a human, your career is over.” Later, when you return to your apartment, McCoy reflects – again, with a tinge of guilt – on the how real the replicant’s desire to live had seemed.

Despite prior knowledge of Blade Runner’s branching storyline and multiple endings, it had never even occurred to me that there might be an option not to shoot Zuben. Indeed, I only found out once I’d played through another few times and consulted various walkthroughs in an attempt to discover the alternative endings I hadn’t been able to discover for myself. But even without thinking that I was allowed to make a choice, I enjoyed the ambiguity of that sequence, and the way the game had treated the aftermath – neither approving of, nor condemning, my actions – left a mark on me.

I soon became rather obsessed with Blade Runner, perhaps even more so than with Wing Commander III, as I threw myself into repeat plays and scoured the internet (in that hot computer room) for tidbits of information. A year later, a friend from school told me he was starting a review site in tribute to some of his old PC favourites, and asked if I had anything to contribute. It was no coincidence that this was the first game I thought of.

Next time: When I played…Deus Ex

Posts

Posts

That is still a damn beautiful game. Blocky characters aside.

I remember being VERY disappointed at the seeming lack of real randomization, probably unfairly so. I guess I was expecting a new game every time.

There was one game though, where the hep cat in the sparkly red coat was a sympathizer, and goaded me into shooting him in the row outside the strip clubs. I took the bait, waddya know, he was a human. Game over with Ray in jail. Never saw that scene again. That’s what I wanted. More of that.

Come to think of it, don’t remember ever having someone pass the VK test (as a human), which was another disappointment. But I also was never fully confident I was giving it correctly.

February 21, 2016 @ 6:23 am

I agree, it still looks great. I was *very* close to just playing through the whole thing again when I went in to grab some shots. (Reminds me, must add some guidance on getting it working in Win 7/8).

I guess my expectations weren’t very high initially because I hadn’t followed the hype, I hadn’t seen the film, and I got my first copy free as part of a bundle. So I probably dodged the feelings of disappointment that many others describe.

At the risk of undermining everything I said in the piece, that guy in the red coat…I could happily have shot him at any point!

February 21, 2016 @ 9:12 am

This is the PC Gamer reveal I remember. Easy to spot what didn’t make it in.

http://media.bladezone.com/contents/game/BR-PCGame1.html

You can see the framework still in the game though. I love the idea that lady Blade Runner (Cheryl? Something like that?) would pick up clues you missed, or use clues you uploaded to the police database to get a jump on your mark (or hunt the reps you’re trying desperately to protect) but it seems all that got turned off, probably in a rush to ship. Or it never actually worked like this article hypes in the first place.

February 21, 2016 @ 4:04 pm

I think Crystal does pick up some clues and upload them, and possibly also takes care of some plot-necessary stuff if McCoy is unwilling, or unable, to do so. But it’s very much in the context of needing something to happen to move the game forward, rather than the free-form investigation advertised in that piece.

February 21, 2016 @ 7:40 pm

Related subject: Did you ever play Snatcher for the Mega CD? Very smart investigation, plus is basically “Blade Runner in Japan.” Think you’d enjoy it.

February 22, 2016 @ 9:22 pm

I haven’t played anything on Mega CD! Would have to look into emulation. Also will check out the JGR review of Snatcher…

Speaking of which, had another read of your Blade Runner review. I’m struck by the fact it never really occurred to me to investigate the mechanics very thoroughly at all, even though (as I say here) I did keep searching for info on the different endings on the internet at the time. Although that information was fairly limited, mainly different walkthroughs from those who’d played it through once and got to a particular ending.

I guess it comes down to expectations again. Or I should have spent a bit more time trying to work things out for myself and understand the game a bit better! Mind you, I wasn’t exactly taking notes in preparation for a write-up as FFG didn’t exist at that point.

February 23, 2016 @ 8:59 am